App Development for Non-Technical Founders: A Step-by-Step Guide

If you’re a non-technical founder, “build an app” can sound like “learn a new language and hire a whole team at once”. This guide walks you through a practical, step-by-step path from raw idea to first working version — without a CTO, without learning to code, and without burning your whole runway. You’ll learn how to define the smallest useful version, choose the right development partner, avoid scope traps, and launch an MVP you can actually put in front of real users and investors.

TL;DR: You don’t need a CTO to build your first product. You need a clear problem, a tiny but useful first version, a small accountable dev team, and a simple way to launch, measure, and iterate. Think in weeks, not years. Focus on “smallest useful version”, not “dream app”. Use partners who speak your language and show progress every week instead of disappearing into code.

Who this guide is really for

This guide is for founders who know their industry well but don’t write code.

You might be a clinic owner, an operations lead, a coach, a consultant, or a specialist who sees the same problem every day and knows it should be automated. You have a clear sense that software could fix it, but no technical cofounder, no in-house dev team, and no desire to manage ten freelancers.

Maybe you already have a deck, a landing page, or a small waitlist. Maybe investors or mentors are asking, “So when will the product be live?” You don’t want to waste 6–12 months and your whole budget on version one. You want a real product in the hands of real users — fast.

If that’s you, this guide is for you.

Start with the problem, not the features

Most non-technical founders start by listing features:

“Login, dashboard, notifications, analytics, AI, marketplace, mobile app…”

That’s how you get a heavy, expensive project where no one is sure what’s truly important.

Instead, start with three simple questions:

What painful problem are you solving, in one sentence?

- “Clinic admins lose hours coordinating appointments manually.”

- “Nurses can’t easily compare job offers across hospitals.”

- “Local service businesses lose leads because requests get buried in WhatsApp.”

Who are your very first users?

- “Ten clinic admins I already know.”

- “Twenty nurses in my Telegram group.”

- “My current customers who already trust me.”

What has to happen in the first 4–8 weeks after launch for this to be a win?

- “At least 10 admins move 50% of their scheduling into the app.”

- “At least 30 nurses create a profile and apply to one job.”

- “At least 20 clients submit an order via the app instead of messaging me.”

Write these answers in plain language, on one page.

This becomes the backbone of your app: a clear story everyone on the team understands. You can always add more detail later, but if you skip this step, all discussions about design, features, and tech stack will be fuzzy.

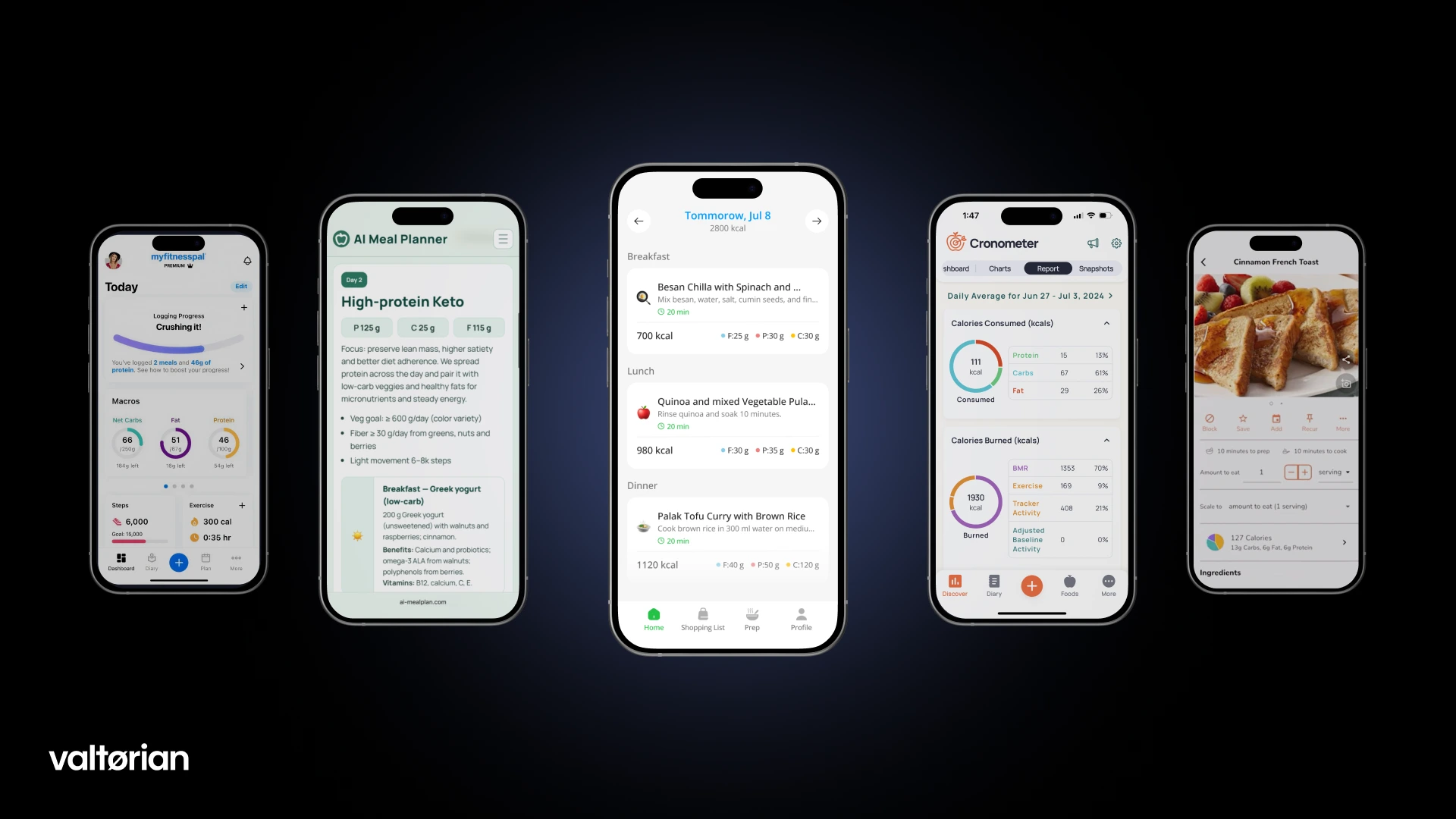

Define the “smallest useful version” (your MVP)

An MVP is not “a cheap, ugly version of your dream app”.

It’s the smallest useful version that lets real users complete one meaningful workflow from start to finish.

To find it, ask:

- “What is the one workflow my first users absolutely need?”

- “What can we safely postpone without breaking that workflow?”

For example, imagine a hiring marketplace:

Core workflow:

- A hospital posts a job.

- A nurse creates a profile and applies.

- The hospital reviews candidates and replies.

If your MVP supports this end-to-end, users can already get real value. They don’t need advanced scoring, badges, in-app video calls, or AI matching on day one.

Split your ideas into two lists:

Must be in v1 (MVP):

- Users can sign up and log in.

- Users can complete the core workflow (post → apply → reply).

- Admin can see activity and export basic data if needed.

Can wait for v2+:

- Ratings and reviews.

- Complex analytics dashboards.

- AI recommendations, scoring, gamification.

- Fancy automation and integrations.

Your goal is not to build the most impressive app. Your goal is to build the smallest app that can prove: “Real people are willing to use this to solve a real problem.”

Choose the right way to build (without a CTO)

You don’t need to become a technical expert, but you do need to choose a realistic way to build your product. For most non-technical founders, there are three paths.

Option A: Build your own dev team

- Pros: full control, potentially a long-term team, deep product knowledge in-house.

- Cons: slow hiring, high fixed costs, you still need a tech lead, and you become CEO + Head of Engineering overnight.

For a pre-seed founder with limited runway, this is often the riskiest option. You lock yourself into salaries before you even know if the product works.

Option B: Work with freelancers

- Pros: lower hourly cost, flexibility, easier to “test” people.

- Cons: you become the project manager, product owner, QA, and sometimes therapist. Different time zones, different styles, and no one truly “owns” the outcome.

This path can work if you already have experience scoping projects, writing tickets, reviewing code, and keeping everyone aligned. If not, it quickly becomes a second full-time job.

Option C: Partner with a small, founder-led studio

- You get a small core team (designer + developers + product lead).

- You work directly with people who have already shipped dozens of MVPs.

- You buy an outcome (MVP in X weeks), not just hours of coding.

For non-technical founders, this is usually the most realistic middle ground: you bring domain knowledge and access to users, your partner brings process, design, and development. You stay in charge of the vision, but you don’t have to coordinate every technical detail.

Whichever option you choose, make sure your partner can:

- Explain tech decisions in plain language.

- Commit to a realistic 4–8 week MVP timeline for your scope.

- Show progress every week (not just “we’re working on it”).

- Tell you “no” when you try to sneak extra features into v1 that will break the timeline.

Turn your idea into a clear, non-technical spec

You don’t need to write technical documentation. You do need a clear brief.

A good structure looks like this:

- Problem & users

- One paragraph describing the problem.

- One paragraph describing your initial users.

- Key jobs (use cases)

Write 3–6 simple sentences:- “As a clinic admin, I want to create a schedule in one place so that I don’t track shifts in multiple spreadsheets.”

- “As a nurse, I want to see all open jobs with clear filters so that I don’t have to DM ten recruiters separately.”

- User flows

Choose 2–3 critical flows (for example: “create job”, “apply to job”, “approve application”).

Describe the steps in plain English:- “User clicks ‘Post a job’ → fills in title, salary, location → saves → job appears on the jobs list.”

- Constraints

- Platforms: web only, mobile first, or both?

- Markets: do you need GDPR compliance, HIPAA, or specific regulations?

- Timeline: do you have a demo day or grant deadline?

- Nice-to-haves

List all extra ideas (AI, scoring, automations, dashboards) here so they’re not lost — but keep them out of the MVP scope.

This document doesn’t have to be perfect. The point is to make your thinking visible so a design/dev team can push back, refine, and price it properly.

Design first, in low risk mode

Before writing any code, you want to “play” with your product as if it already existed. That’s what good UX/UI design gives you.

A healthy design phase usually includes:

1. Wireframes

These are black-and-white layouts that focus on structure, not beauty.

You’re answering questions like:

- “Is it obvious where to click next?”

- “Do we collect too much data on one screen?”

- “Is this flow shorter than the way users do it now?”

At this stage, it’s completely fine if buttons are gray rectangles and logos are placeholders.

2. Visual design

Once the structure feels right, you add:

- Colors, fonts, and basic components.

- A simple design system: buttons, inputs, headings that repeat across the app.

The goal is to look clean and trustworthy, not to win a design award. Consistency is more important than complexity.

3. Clickable prototype and quick user feedback

Your design team can turn the key flows into a clickable prototype (for example, in Figma). You can send a link to early users and watch how they move through the app.

Simple questions to ask them:

- “What’s confusing on this screen?”

- “Where did you expect to click?”

- “What would stop you from using this in your real work?”

It’s much cheaper to fix confusion in a design file than after a month of development.

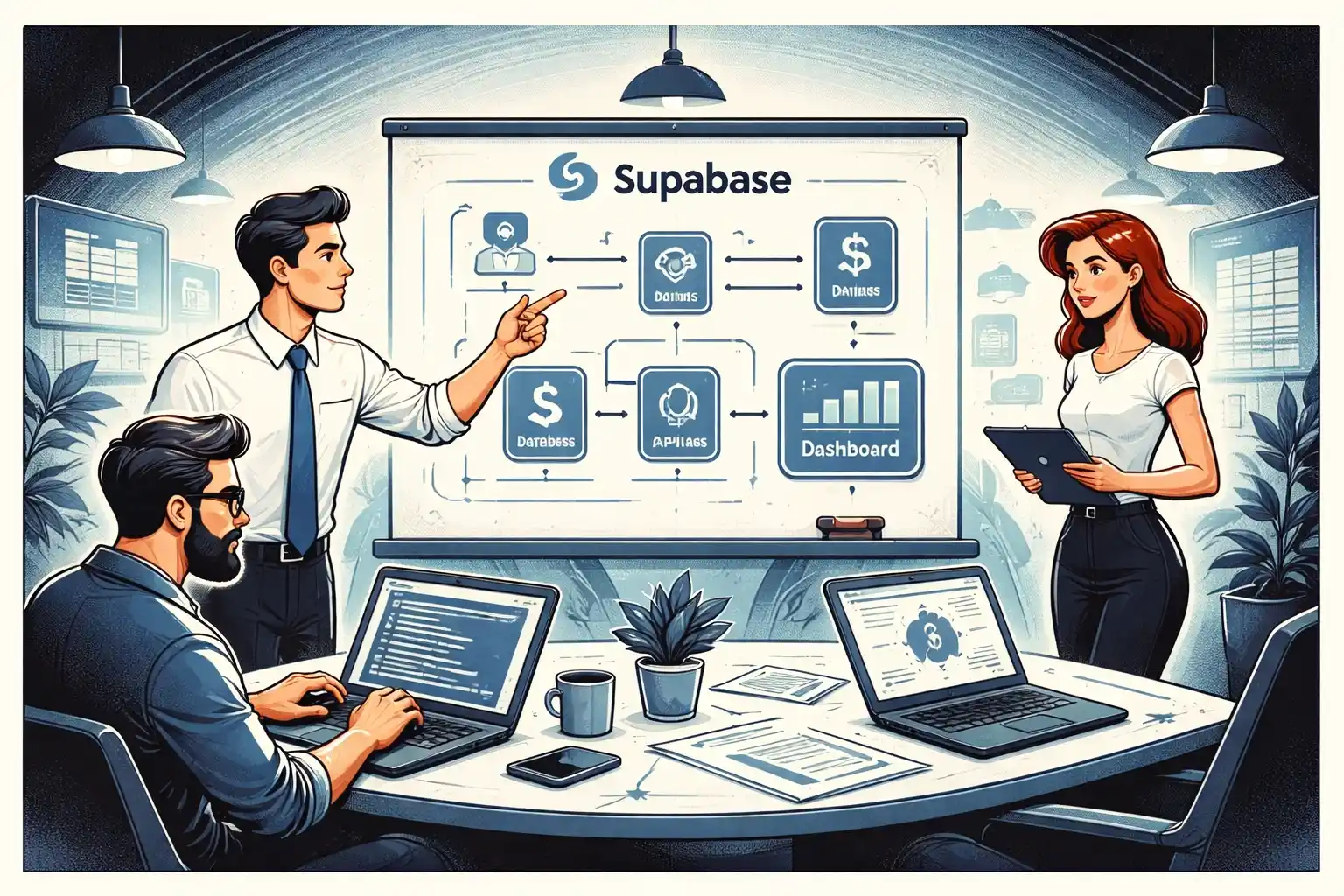

Development when you’re not technical — how it should feel

Development should not feel like a black box where you throw money in and hope for the best. Even if you’re not technical, you can expect a clear, transparent process.

Clear tech choices (without jargon overload)

Your team should briefly explain:

- What stack they use (for example, React / Next.js, Flutter, Node, Supabase, etc.).

- Why it fits your stage: fast to build, easy to maintain, scalable enough for the first 6–18 months.

- Any limitations you should be aware of.

You don’t need to understand every acronym. You do need to understand trade-offs: “This choice makes it faster to launch”, “This will make analytics easier later”, “This integration will take extra time”.

Short cycles, visible progress

Instead of a 3-month silence, you want:

- Weekly or bi-weekly demos where you see real screens, not just hear status updates.

- A simple summary:

- What’s done.

- What’s in progress.

- What moved out of MVP to protect the timeline and budget.

These short cycles keep everyone honest and make it easier to adjust scope if something turns out more complex than expected.

One source of truth

Ask your team to keep one living board (Notion, Jira, Trello — the tool doesn’t matter) that shows:

- The MVP scope (list of features and flows).

- The status of each item.

- Known bugs and technical tasks.

- Decisions made (“We removed this from v1 because…”).

As a non-technical founder, you should be able to open this page and immediately see where your project stands.

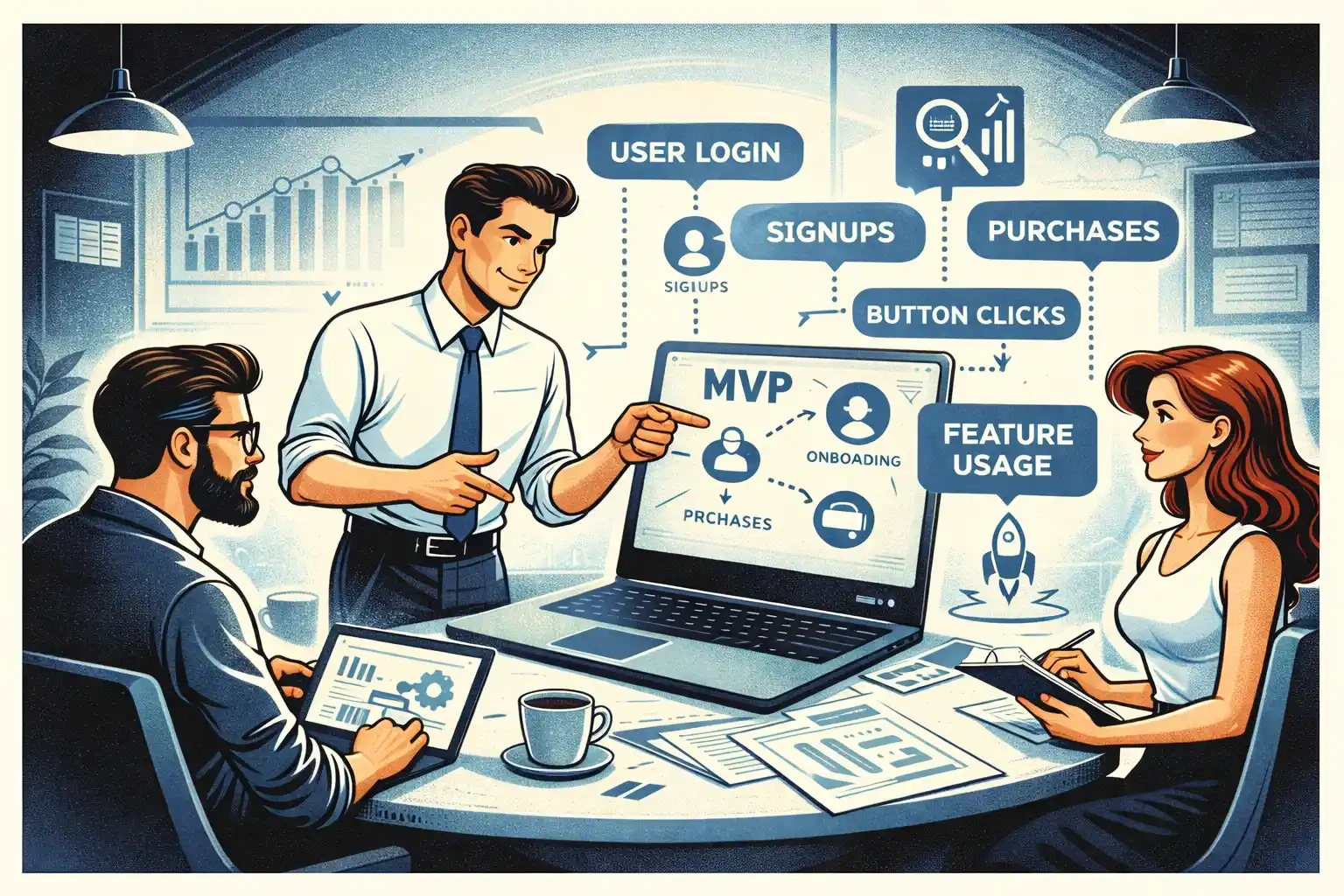

Launch, measure, and learn

Launch is not the finish line. It’s the start of real learning.

Before you ship, decide on three things:

1. How users will find your app

Pick at least one specific channel:

- Your existing clients and contacts.

- Your LinkedIn network.

- Founder communities, industry groups, or niche Slack/Discord servers.

- A small paid test (for example, running a simple ad to your target audience).

“Build it and they will come” almost never works. “Build it and actively invite them” does.

2. What you will measure in the first 30–60 days

At minimum:

- Signups: how many people start?

- Activation: what counts as “really used it at least once”? (for example, “created one job and received one application”).

- Retention: how many users return in week 2 or week 4?

You don’t need a huge analytics setup. A few key events and a clear idea of what “success” looks like are enough at this stage.

3. How you will collect feedback

Combine numbers with conversations:

- Short in-app surveys after key actions.

- Manual calls with your most engaged early users.

- One simple question after the main flow:

- “What almost made you give up?”

- “What was more confusing than it should be?”

Your MVP is a test. The goal is not to get everything right. The goal is to learn fast enough to make smart next decisions.

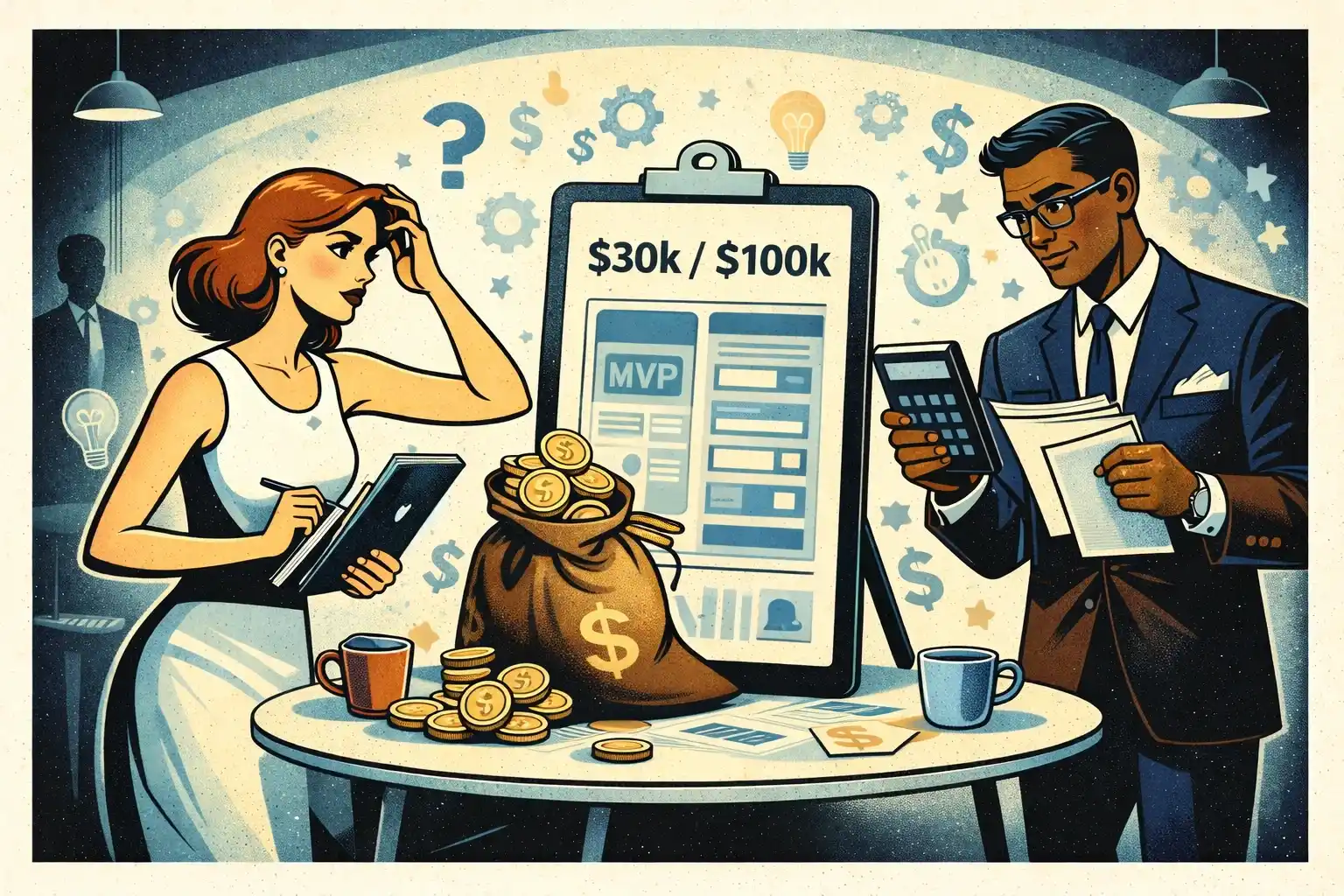

Timelines and costs — what’s realistic?

Every project is different, but for early-stage B2B or B2C SaaS, healthcare tools, or simple marketplaces, a realistic MVP plan often looks like:

- 1–2 weeks – Clarify idea, users, success metrics, and MVP scope.

- 2–3 weeks – UX/UI design and clickable prototype with at least one round of user feedback.

- 3–5 weeks – Development, testing, final fixes, and launch.

In total, you’re looking at roughly 6–10 weeks from “we agreed on scope” to “people can use it”.

On cost, many early MVPs end up roughly in the $10k–$30k range, depending on:

- Number of platforms (web, iOS, Android).

- Complexity of flows.

- Third-party integrations (payments, calendars, healthcare systems, etc.).

- Security and compliance requirements.

The important part: you should know what you’re getting for that budget. A good partner will always tie cost to a clear scope and explain where the money is going.

Common mistakes non-technical founders make (and how to avoid them)

Mistake 1: Copying a mature competitor on day one

You look at a mature SaaS with 50 features and think: “We need all of that, just simpler.”

You don’t. They are on version 20. You are on version 1.

How to avoid it: identify the one or two jobs that make your product worth using. Build only those in v1.

Mistake 2: Treating devs like magicians, not partners

You say: “We want an AI marketplace app like X”, and expect the team to guess the rest.

How to avoid it: bring your domain knowledge to the table. Explain real-life scenarios, examples, and constraints. Let your dev/design partner propose options and push back on scope.

Mistake 3: Hiding uncertainty

You feel pressure to pretend you have all the answers about pricing, features, and business model.

How to avoid it: say where you’re unsure. A good team will design the MVP so that you can test different prices, messages, or flows without rebuilding everything.

Mistake 4: Over-focusing on technology

You get stuck on questions like “React Native or Flutter?” or “AWS or GCP?” without understanding how that connects to your business.

How to avoid it: focus on business questions: speed, flexibility, runway, and user experience. Let your technical partner pick the tools that fit those constraints and explain the reasoning in simple terms.

Mistake 5: No plan beyond launch

A surprising number of founders believe “once the app is live, investors will show up.”

How to avoid it: decide before development how you will onboard the first 20–50 users, what you’ll measure, and how you’ll decide whether to double down, pivot, or stop.

What to do next

If you remember only three things from this guide, make them these:

- Think in workflows, not features.

Your MVP should let your first users complete one meaningful job from start to finish. Everything else can wait. - Choose a partner, not just a tech stack.

Tools matter, but for a non-technical founder, the team matters more. Look for a small, accountable, founder-led team that has shipped real products in your stage and can speak your language. - Ship, learn, adjust.

Version one is not your final product. It’s your first serious experiment. You want it in weeks, not years.

Your very next step can be simple:

- Write a one-page brief using the structure from Step 4.

- Share it with a potential development partner.

- Ask: “What would a 6–8 week version of this look like?”

The answer to that question often reveals which parts of your idea really matter — and which can wait.

Ready to build your MVP with a small, senior team instead of hiring a full tech department?

At Valtorian, you work directly with the founders — the people who have designed and delivered over 70 products and know how to ship fast without breaking quality.

If you already have an idea or early prototype and want to understand what an MVP version could look like in your case, let’s discuss it together.

Book a call with Diana (Product Delivery Lead)

We’ll walk through your idea, clarify the core workflow, and outline a realistic path to launch.

FAQ: App development for non-technical founders

Can I really build an MVP without a technical cofounder?

Yes. You need a clear problem, access to real users, and a partner who can translate your idea into a realistic scope, design, and implementation. Many successful founders bring in technical cofounders later, once the product already has traction.

How long does it usually take to build an MVP?

For a focused, well-scoped MVP, 6–10 weeks is typical: 1–2 weeks for scoping, 2–3 weeks for design, and 3–5 weeks for development, testing, and launch. Very complex products or heavy integrations can take longer, but if someone quotes 9–12 months for your first version, it’s worth asking why.

How much should I expect to invest in an MVP?

Most early-stage MVPs for web or mobile end up in the $10k–$30k range, depending on complexity, number of platforms, and integration requirements. The key is having a clear scope so you know exactly what you’re paying for and what “done” means.

How do I decide what goes into the MVP and what can wait?

Use a simple rule: if the feature is required to complete the core user workflow, it’s MVP. If it’s “nice to have”, it goes into the later list. It’s better to have one workflow that works reliably than five that are half-broken.

Do I need native mobile apps from day one?

Not always. For many products, a responsive web app or a single platform (iOS or Android) is enough to validate demand. Native apps make more sense when your users truly need on-the-go access, offline mode, or deep device integrations.

What are the risks of working with freelancers or large agencies?

With freelancers, the main risks are coordination, lack of ownership, and dependency on individuals. With large agencies, the risks are slow processes, layers of communication, and being a small client in a big portfolio. A small, experienced team focused on MVPs can often deliver faster and with more attention.

Can you help me refine my idea and user flows, not just code?

Yes — and for non-technical founders, this is often the most valuable part. A good partner will help you clarify your idea, choose a realistic MVP, design user flows, and prepare you for launch and early traction, not just “deliver an app”.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)